Diminutions: A Practical Guide to Getting Started (and Moving Forward)

Adapted from my article in American Recorder, Vol. LXIV, No. 4 (Winter 2023); also published in Recorder Magazine and Windkanal (DE).

Why diminutions (not trills)?

If you want to ornament Renaissance and early 17th-century music, you don’t reach first for a trill—because trills belong to the later Baroque ornamental language. Instead, the technique of diminutions (also called passaggi, glosas, divisions) is the right tool. This guide gives you a historical snapshot, the main ornament types, and step-by-step practice tips so you can start ornamenting musically and confidently.

What are diminutions, and what do they achieve?

In treatises and performance practice, diminutions subdivide long notes into a chain of shorter ones—but in a way that preserves the line, not obscures it. (E.g. Michael Praetorius defines “diminution” as “breaking up and resolving of a long note into many faster and smaller notes.”)

The ornament is horizontal: it carries the musical idea, rather than interrupting it. The effect is that it extends the original tone’s expressive capacity—gives it color, momentum, nuance.

The term passaggi (Italian for “passages”) reminds us that the ornament is often not tied to a single note, but to a stretch of melody—“filling it up” in a way that still lets the listener hear the skeleton. (This is distinct from a short grace note or a “turn” that decorates one pitch.)

Because ornamentation in Renaissance music is deeply tied to text, phrasing, rhetoric, diminutions were often designed around cadences, word stress, contour. They were an expressive extension of what the composer (or singer) already intended, not an added “extra.”

Over time (late 16th → early 17th), ornament vocabulary expands. The newer style allows more rhythmic variety, dotted figures, and looser figurations—but diminutions remain foundational.

Key contrast: When trills appear (and why they are different)

Trills, as we commonly think of them (rapid alternation with the upper neighbor, onset from the upper note, etc.), emerge in the Baroque ornamental grammar. They express local tension/continuity more than melodic subdivision across a span.

In pre-Baroque repertoire, a trill would be seen as too “vertical” or disruptive; the flow of the line was central.

Thus, instead of “trilling a long note,” early musicians expected diminutions—“painting” or “walking through” it—filling it out with expressive motion.

A bit of history

Renaissance (1500s): players improvised florid lines by subdividing long notes. Treatises not only explain how, they also include written-out models, which are compositions in themselves.

Ganassi, La Fontegara (1535): complex, virtuosic, almost 15th-century-style divisions.

Ortiz, Tratado de glosas (1553): clear, versatile, and practical—still one of the best how-to guides.

Later treatises (second half of the century):

1580s: Bassano — flowing, idiomatic writing.

1580s: Dalla Casa — somewhat dry, “scholarly” and mental in approach.

1590s: Riccardo Rognoni (father of Francesco Rognoni di Taeggio) — expressive, inventive, often strikingly beautiful diminutions.

1590s: Conforto — practical, promising you could learn the craft “in three months.”

1590s: Also Bovicelli, the one who is mentioned afterwards.

Bridge to the new style: Bovicelli (1594) — already shows the shift toward declamation and affect; diminutions often fall on penultimate syllables to keep words clear.

Toward 1600 (stile nuovo): Music takes a dramatic turn. The first operas appear, monody with basso continuo becomes the norm, and instrumental genres (sonata, canzona, toccata, fantasia) develop. Ornamentation diversifies: rhythms freer, affect and declamation matter more than symmetry. Authors like Caccini, Brunelli, and Francesco Rognoni di Taeggio expand the palette with expressive, affect-driven nuance.

How to begin (the two golden rules)

When you first try diminutions, two principles will keep you on track:

Articulate (don’t slur)

Diminutions should be clear and lively, not blurred. They’re usually quite fast, so use a light double-tongue (e.g., de-ge or did’l). The key is that your air remains one horizontal, singing line—as if you were sustaining the original long note. Think of the air as the motor and the tongue as simply riding on it.

Favor stepwise motion (seconds)

Diminutions are supposed to move mostly by step (in seconds). Avoid arpeggio patterns, which are more characteristic of later styles. When you do leap, make sure it’s from one consonant to another within the harmony (e.g., 1–3–5–8), and then return to stepwise motion.

A historical side note: the trill as we know it in the Baroque era (starting from the upper note, decorative shake) did not exist yet in mid-16th-century practice. Cadential ornaments were still diminutions, not trills.

Diego Ortiz’s three “ways to diminish” (1553) — your starter toolkit

Way 1 (safest): begin and end the figure on the original note, then move on. This preserves the counterpoint intact and is the best starting point.

Way 2: begin on the original, then flow directly into the next note by step. You may create passing dissonances or parallels, but they pass too quickly to jar.

Way 3 (free): expand into a longer span or replace a main melodic note with a coherent sequence or motivic idea—but only if you know what the other voices are doing (aim for contrary motion when possible).

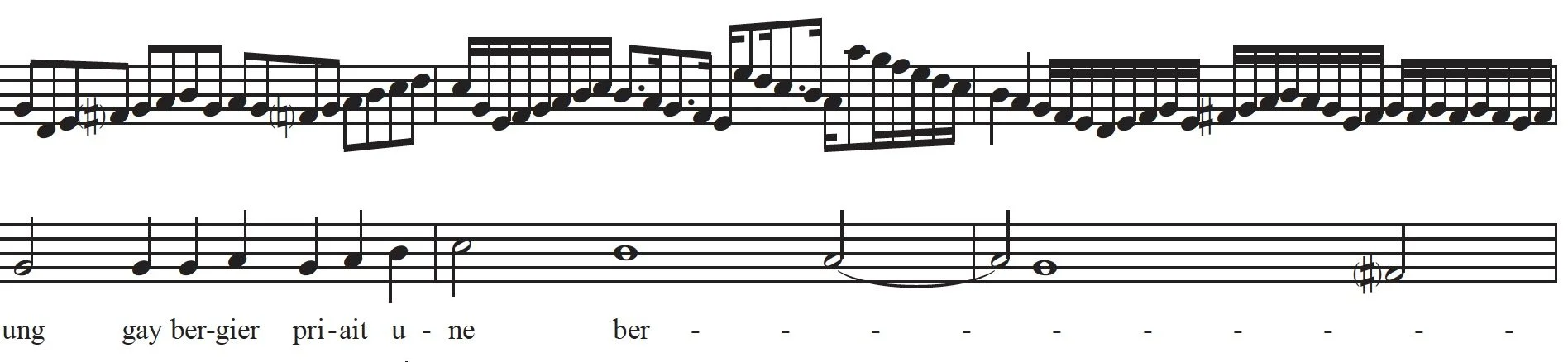

Ex. 1–3 (Rognoni, Ung gay bergier) Three basic approaches to diminution:

Begin and end on the same note.

Begin on the note, then flow by step into the next.

Freer substitution or sequential figure (requires awareness of other voices).

Tempo & tactus

Before barlines were standard, players relied on the tactus—a steady, natural pulse—and allowed flexing subdivisions (duple ↔ triple) over it.

In the mid and late 16th-century practice, diminutions usually flow in even, regular values that preserve the tactus.

By the early 17th century, with the stile nuovo, diminutions (and ornaments in general) tend to play more with rhythm: more variety, more affect, and occasional flexibility in tempo — but always grounded in the pulse.

Core ornament types (16th & early 17th c.)

16th-century essentials:

Passaggi (general diminutions): connect melody notes primarily by step.

Groppo (cadential group): alternation in seconds with a little turn at the end.

Tirata (Praetorius): a long, rapid, graduated run up or down.

Ex. 4–6 (Rore/Rognoni, Ancor che col partire) 16th-century essentials

New/expanded in the 17th century:

Trillo (not the later Baroque trill): repeated articulations on a single pitch—Caccini’s ribattuta di gola. On recorder, this can be:

a light double-tongue “bouncing ball,” gradually quicker, leaving the last note to ring;

finger vibrato with the same accelerating feel;

or lifting a finger in a dotted pattern that speeds up (sometimes trill-like, but conceptually different).

Accento (passing-note figure): two kinds of pattern—ascending (esp. thirds) and descending (seconds). Best used where full diminutions would feel too much: intense emotional spots or the opening of imitations.

Groppo rafrenato (Bovicelli): fast notes slowing down just before the resolution.

Messa di voce: controlled crescendo–decrescendo on a sustained note.

Dotted diminutions (lombardic patterns): long–short / short–long rhythms, considered especially graceful.

Tremolo: a “shaking of the voice”—a vibrato-like effect, but only used as an ornament.

Ex. 7 and 8 (Bovicelli, Io Son Ferito) Some examples of the new ornaments

Build diminutions into daily practice

Study the originals first. Sing or play the source melody first; if there’s text, follow its phrasing. (These were the “hits” of their day—imagine diminishing Yesterday: you’d notice instantly if the diminutions went against the song.)

Play through historical examples. Ortiz’s glosas (and his grounds), Rognoni’s sets, etc. Notice where each author uses passaggi, groppi, accenti, or dotted figures.

Useful tools:

Passaggi (app): accompaniments for Ortiz and other authors, drones, and tracks for historical pieces.

Embellishment Workout (Cat on the Keys).

Philippe Matharel’s L’Art de Diminuer — an interval-by-interval anthology.

Original treatises on IMSLP, vocal pieces on CPDL

Ex. 9 (Rognoni, Ung gay bergier)

Playful diminutions that reflect the light and witty nature of the text.

A from-scratch roadmap (try this on a simple chanson or pavane)

Good starters: “Belle qui tiens ma vie” (Arbeau) or “Triste España” (Encina).

Decorate the obvious first: cadences, clear contour changes.

Example: D–E → D c d E (fill the step).

Start small: add 1–2 notes; gradually extend. Build stepwise bridges between structural notes.

Choose an easy tactus: never faster than your brain can track; stay relaxed.

Honor the phrasing/text & genre: breathe where a singer would; is it a madrigal, chanson, pavane? Let that style steer you.

Reuse motives (on purpose): repetition creates cohesion. Vary by rhythm, transposition, or sequence when you need contrast.

Give the opening space: many sources don’t ornament the very first note—let the line speak, then decorate.

Keep rhythms even: avoid “a long note… then a burst of tiny notes… then again a long note.” Distribute notes regularly across the span.

Prefer simplicity: don’t stray far from the skeleton. A handy check: aim to return to a written pitch by halfway through the span.

Mind the counterpoint: glance at the other voices—avoid parallels/voice-crossing (if you’re the top voice, generally don’t dip more than a fifth below).

Don’t decorate the last note of a phrase—unless you’re making a bridge into the next (à la Rognoni’s Vestiva i colli).

If the melody repeats, leave room for more: start modest; grow the diminutions on later statements.

For 17th-century style: introduce dotted figures, trilli, messa di voce, etc.

Ex. 10. Rognoni, Vestiva i colli

A bridge between two phrases

And remember: this is improvisation. It won’t be perfect every time—that’s the fun. You’re puzzling musically from point A to B; with practice, the paths multiply and feel natural.

Quick articulation reminder

Diminutions succeed or fail on the balance of air and tongue. Keep the air steady, think of a continuous line, let the tongue stay light (e.g., de-ge/te-ke or did’l), and aim for stepwise fluency rather than flashy leaps.

Useful resources

IMSLP (treatises & facsimiles): imslp.org

CPDL/ChoralWiki (original vocal sources): cpdl.org

Passaggi app (Ortiz accompaniments, drones): passaggi.co.uk

Embellishment Workout (Cat on the Keys): catonthekeysmusic.co.uk

Matharel – L’Art de Diminuer (compendium of historical diminutions filling different intervals)

Our CD-album Pulchra es with diminutions, sonatas & canzonas: lobke.world/pulchra-es